Smithsonian Dismantling African American Exhibits Amid Trump-Era Pressure

In a move that has sparked outrage among civil rights leaders and historians, Trump officials are reportedly dismantling Smithsonian exhibits that highlight African American history—starting with the iconic 1960 Woolworth’s lunch counter sit-in display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, affectionately known as the “Blacksonian.”

The exhibit, which includes the original lunch counter from Greensboro, North Carolina, tells the story of four Black students from North Carolina A&T State University who staged a sit-in at a Whites-only counter. Their peaceful defiance on February 1, 1960, became a catalyst for lunch counter protests across the South and a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement.

North Carolina Representative Alma Adams did not mince words in her response:

“This president is a master of distraction and is destroying what it took 250 years to build. Here’s another distraction in his quest for attention — another failure of his first 100 days.”

Adams warned that attempts to physically erase parts of America’s history will not succeed:

“You can take down exhibits, close buildings, ban books, and try to change history, but we are long past that point. We will never forget.”

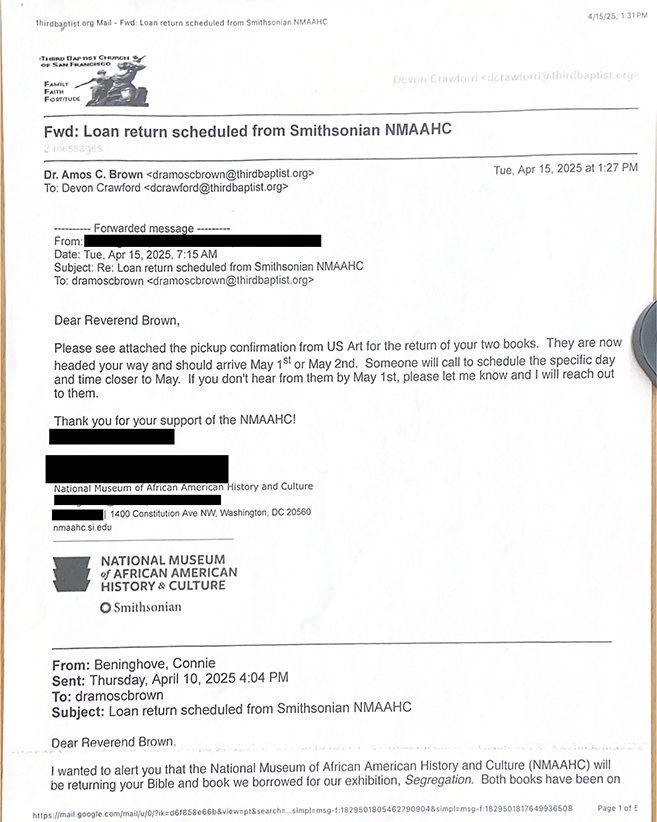

Behind the scenes, artifacts loaned by civil rights veterans are quietly being returned. Black Press USA obtained a letter addressed to Reverend Dr. Amos Brown — civil rights leader and pastor of San Francisco’s Third Baptist Church, famously known as the home church of former Vice President Kamala Harris. The letter notified Brown that his father’s Bible and a rare copy of “History of the Negro Race in America, 1618-1880” by George W. Williams would be returned.

In an emotional reflection, Rev. Brown described the profound personal significance of these artifacts:

“That book inspired me before African studies programs even existed. In my home, at 3rd Street Baptist Church, we studied that book. The Bible—that’s my father’s Bible and the Bible I carried in the Civil Rights Movement. We always had it with us at demonstrations.”

The artifacts had been on display at the museum since its grand opening in September 2016, anchoring key exhibits alongside figures like Medgar Evers, John Lewis, and Fred Shuttlesworth.

Reshaping National Memory

Meanwhile, the future of African American history at the Smithsonian is facing further threats. Attorney Lindsey Halligan, who is advising Vice President JD Vance on culture policy, has been tasked with recommending changes to museum exhibits. According to a Washington Post report, Halligan is pushing to “remove improper ideology” from Smithsonian properties.

Halligan’s stated aim is to downplay narratives that, in her words, “overemphasize the negative.” She argues that focusing too much on the darker chapters of American history “just makes us grow further and further apart.”

The move has drawn fierce criticism from educators, historians, and civil rights advocates who view it as an effort to sanitize history and weaken public memory of systemic injustice.

For leaders like Rep. Adams and Rev. Brown, the removal of historic exhibits isn’t just an administrative decision—it’s an attack on the hard-fought battles for visibility, truth, and dignity.

As the Smithsonian quietly returns artifacts and political operatives maneuver to reshape historical narratives, the fight over who gets to define America’s memory is far from over.