The Stolen Inheritance: California’s Early Black Settlers Lose Land, Descendants Seek Restitution

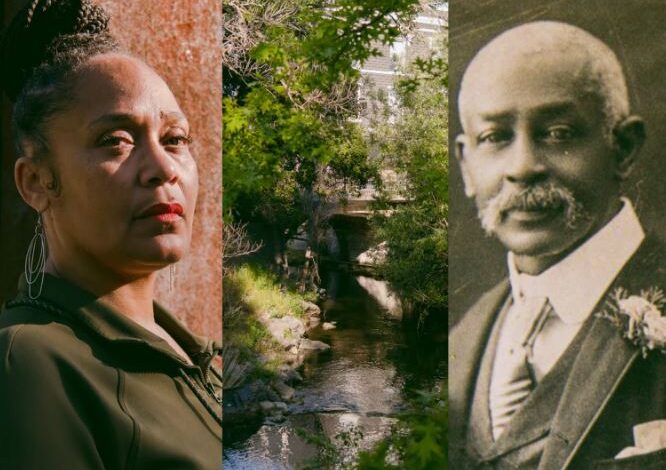

On a quiet evening at her Sacramento home, Yolanda Tylu Owens, after nine months of diligently researching her family tree, experienced a remarkable moment of ancestral connection. Sitting at the foot of her bed, an unexpected idea flickered in her mind, as if whispered by her predecessors.

“It felt as though my ancestors were speaking directly to me,” Owens shared. “The thought came out of nowhere, but it was crystal clear: I needed to investigate whether my great-great-great-grandfather owned any land.”

Driven by this newfound inspiration, Owens swiftly reached for her laptop. Within minutes, she found herself leaning back in her chair, trying to absorb the astonishing information she had just uncovered.

“It was right there, unmistakable,” Owens recounted. “Four deeds registered under his name, indicating his ownership of land.”

But this was no ordinary land; it was located in Napa, California, renowned as America’s most prestigious wine-growing region, exuding opulence and natural splendor. Three of the deeds revealed that her ancestor, Edward Hatton, possessed valuable properties on Main Street in downtown Napa, while the fourth deed encompassed a vast expanse of 209 acres in the neighboring mountains.

Owens’ remarkable discovery not only shed light on her ancestor’s land ownership but also raised questions about its potential confiscation—an aspect that aligns with the ongoing efforts in California to consider reparations for Black individuals.

The exploration of historical injustices and the possible restitution for African Americans in California has gained significant traction in recent years. The acknowledgment of past wrongs and the examination of their lasting effects have prompted the state to explore reparations as a means of redress.

Owens’ ancestral findings add a personal dimension to this broader narrative, emphasizing the need to address the historical inequities faced by Black Californians. The loss of land, a common occurrence during times of racial discrimination and systemic oppression, serves as a reminder of the profound economic and social disparities experienced by Black communities throughout history.

As the movement for reparations gains momentum, Owens’ discovery serves as a poignant reminder of the long-lasting consequences of past injustices. By delving into her family history, she not only unearthed her ancestors’ struggles but also contributed to the collective understanding of the need for restorative measures to rectify the imbalances faced by Black individuals and communities in California.

As for the large piece of land in the outskirts of Napa, Owens said the Hattons bought the 209 acres for $1,500 in February 1885. According to her research from various documents and news clippings, white people wanted the land, and in 1893, a white woman claimed the Hattons had defaulted on a $400 payment. The land was later put up for auction at a court hearing at which the Hattons were not present. The woman bought it and then sold it to the county treasurer at the price she had paid for it. “The treasurer, who had already owned other large parts of that mountain, put the land in her own name, and that was that,” Owens said. “They stole it.” Soon, an upscale restaurant the Hattons owned, The Arcade, was burned down, Owens said, and her ancestors fled Napa. Thomas Mitchell, a Boston College Law School professor, said that once Black people began to acquire land after having been enslaved, it was considered the norm in the years following the end of slavery for that land to be seized without provocation or justifiable reasons, “for it was considered better and higher economic use of the property.” The practice underscored “that notion that we had to accept that Black people’s lives are just not that important,” said Thomas, a 2020 MacArthur Fellow. “Their property ownership and their communities are not as important. They should be ready to have their rights sacrificed for the ‘greater good.’” In 1867, Edward Hatton wrote a letter to the editor of The Elevator, a defunct local Black newspaper, that said, in part: “Why should we of this State be treated with so much injustice? Are we not as intelligent as any class of the community, and are we not taxed as well as others? Why this distinction? I think it is time we should be doing something for ourselves.”

Regarding the expansive parcel of land on the outskirts of Napa, Owens shared that the Hatton family had purchased the 209 acres in February 1885 for $1,500. Owens painstakingly pieced together her research from various documents and news clippings, revealing a disturbing tale of racial injustice. It became apparent that white individuals coveted the land, leading to a series of events that culminated in the Hatton family’s loss of their property.

According to Owens’ findings, in 1893, a white woman alleged that the Hattons had defaulted on a $400 payment. Subsequently, the land was put up for auction during a court hearing where the Hattons were not present. The woman purchased the land and then sold it to the county treasurer at the same price she had paid for it.

“The treasurer, who already possessed other significant portions of that mountain, registered the land under her own name, and that was the end of it,” Owens lamented. “They stole it.”

Tragically, not long after these events, an upscale restaurant owned by the Hatton family, The Arcade, was set ablaze, forcing Owens’ ancestors to flee Napa in fear for their lives.

Thomas Mitchell, a professor at Boston College Law School, shed light on the prevalent practice of seizing land from Black individuals without just cause following the end of slavery. He explained that during that period, it was deemed acceptable to confiscate land from newly freed Black people under the pretext of achieving “better and higher economic use of the property.”

This practice underscored a deeply ingrained notion that Black lives and their possessions held lesser value. Mitchell stated, “It perpetuated the belief that Black people’s lives are simply not as important. Their property ownership and communities are deemed less significant. They were expected to be prepared to sacrifice their rights for the so-called ‘greater good.'”

In 1867, Edward Hatton penned a letter to the editor of The Elevator, a now-defunct local Black newspaper. In his letter, Hatton questioned the injustice faced by the Black community, highlighting their intelligence, equal tax contributions, and the need for self-empowerment. He expressed a growing sentiment that it was time for Black individuals to take action and advocate for themselves.

Hatton’s poignant words, written over a century ago, echo through time, reflecting the enduring struggle faced by Black Americans in their fight for equality, justice, and the preservation of their rights.

Owens’ discovery of her ancestors’ land loss serves as a painful reminder of the systemic discrimination and dispossession endured by Black communities in California. Their experiences highlight the urgent need for reparations and restorative measures to rectify the generational harm caused by slavery and systemic racism.

As California’s reparations task force works toward addressing historical injustices, the stories of families like the Hattons serve as potent reminders of the long-standing inequities that continue to shape the lives of Black individuals today. Through their resilience and determination, these families contribute to a broader movement seeking redress, ensuring that the pursuit of justice remains at the forefront of the collective consciousness.