What can be done about the underfunding of land-grant HBCUs by states?

It is the opinion of many that land-grant HBCUs have received billions less in funding than their white counterparts. Advocacy from the Black community can play a role in ensuring that the shortages are addressed through the renewal of the farm bill this year.

HBCUs have historically received significantly less funding and access to resources when compared to predominantly white colleges and universities. Despite experiencing historic increases in enrollment, HBCUs remain financially depleted and under-resourced, while their predominantly white counterparts enjoy multibillion-dollar endowments and vast resources that sometimes amount to billions of dollars.

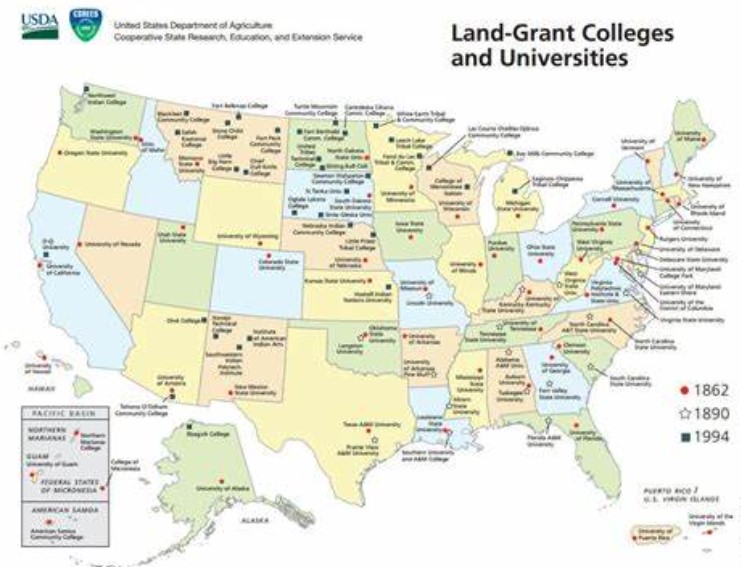

Among the nation’s land-grant institutions, which were established by Congress with the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890, there is a clear example of underfunding in HBCUs. The states were given federal land by the federal government to finance and establish land-grant colleges.

The root cause of the resource disparity between predominantly white institutions (PWIs) and the 19 HBCUs that are land-grant institutions can be attributed to a racial funding gap. There are those who would refer to it as theft, specifically the act of taking billions of dollars in federal and state government funding from Black institutions. This is a case of racism that has been deeply rooted in the system for 150 years, and there is evidence to support it. Hence, a vast number of land-grant HBCUs are encountering difficulties. All of that could be changed by the federal farm bill.

The Morrill Land Grant College Act was enacted in 1862 and named after Senator Justin Morrill of Vermont. It granted 30,000 acres of public land to each state to establish or enhance public colleges and universities, both new and existing ones, that would benefit agricultural and mechanical arts. Land and money were provided to support and maintain these institutions. Among the land-grant institutions are Clemson, Cornell, Iowa State, MIT, the University of Missouri, Nebraska, Rutgers, Washington State, and the University of Wisconsin. The funding of higher education by the federal government was a new initiative.

Nevertheless, Morrill Act 2.0 became necessary in 1890 to include African Americans. According to theGrio, Tennessee State Rep. Harold Love, Jr. said that Morrill did not expect certain states to give out land grants and exclude African Americans from admission. Rep. Love stated that a second Morrill Act, aimed at addressing the defeated South after the Civil War, would be identical to the first one, except for the provision that states could not discriminate against individuals of a certain race when it came to university admission.

The establishment of 19 HBCUs, including Alabama A&M, Alcorn State, Central State, Delaware State, FAMU, Fort Valley State, Kentucky State, Langston, North Carolina A&T, Prairie View A&M, South Carolina State, Southern, Tennessee State, Tuskegee (the only private land-grant HBCU), University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, University of Maryland Eastern Shore, Virginia State and West Virginia State, was a result of the 1890 Morrill Act.

Although the federal government has mandated states to provide an equal amount of funding as them to the Black land-grant universities, there are certain states that have not complied with the one-to-one match formula and have continuously provided insufficient funds to these HBCUs. For a number of years, these schools did not receive any funding from the state. These colleges may lose their federal funding if they do not receive a waiver from the federal government or obtain matching state funding. States maintain the one-to-one funding standards for predominantly white 1862 land-grant colleges consistently and usually surpass them while decreasing funding for 1890 HBCUs in the same state.

State Rep. Love took on the responsibility of addressing unequal funding at Tennessee State University, following in his father’s footsteps.

Upon review of the data, he discovered that Tennessee State University had been underfunded by $544 million since 1957. This underfunding was responsible for Tennessee State’s inability to maintain its buildings for two decades, which exacerbated existing problems. The amount of $544 million could have been allocated to the endowment, teacher salaries, and scholarships. Love said that the possibilities were numerous for where it could have gone.

The Nashville lawmaker added that it is a scenario in which you are aware of the existence of something, but are unable to pinpoint it. It’s like being sick, so folks wouldn’t know. You feel unwell, but you’re unable to identify the source. Currently, our focus is on diagnosing and identifying the exact problem so that a solution can be developed.

Per a Forbes inquiry conducted in 2022, the HBCUs that were granted land are entitled to at least $12.8 billion owed to them from the previous 30 years. This includes a minimum of $1.9 billion for TSU, which includes the cost of missed opportunities. The private industry also fails to invest in these institutions.

Dr. Mortimer H. Neufville, CEO and president of the 1890 Universities Foundation, points out that the existence of a funding gap has actual consequences for HBCUs as they strive to improve their positions among research universities and become top-tier institutions with substantial endowments and Ph.D. faculties. The 1890 land-grant universities receive support for education, outreach, and academics from nonprofit organizations classified under 501(c)(3). “We are secret in the states that is well-kept and considered the best.”

Neufville emphasized that the land-grant HBCUs require knowledge and must possess it. We have consistently been expected to accomplish more with limited resources. This is still ongoing at the present time. We have consistently been expected to improve our situation without external assistance. “Prior to anything else, the boots are necessary.” As per State Rep. Love, inequalities have been ingrained in the system and established right from the beginning. We need to educate our colleagues and individuals who have the perception that we constantly accuse people of racism, and that this is not the case. To bring about a change in inequity, there must be a critical moment when enacting legislation for it to happen.

Love is optimistic that the public will be given a chance to have conversations with lawmakers regarding the future course of action. A conversation is necessary to initiate it. “I was fortunate to have a blueprint from my father which I extended,” he explained, providing a toolkit that other HBCUs can use to regain the resources that were withheld from them. Maryland’s four HBCUs have been awarded $577 million after a 15-year legal battle claiming that the institutes were not given equal resources, raising hope.

TSU has been granted $250 million to restore its campus infrastructure.

The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, also known as the 2018 Farm Bill, will expire this year. This bill provided $40 million for scholarships to land-grant Black colleges and universities for secure resources. The primary federal tool for funding land-grant institutions, which include land-grant HBCUs, is legislation. Neufville thinks that the solution to the underfunding of the 1890 institutions lies in a renewed farm bill that will be passed later this year.

“There is an opportunity to examine the farm bill and inquire of Congress about their level of dedication to enhancing social mobility, aiding underserved communities, and ensuring access to food and healthcare for all. “The Farm Bill can effectively tackle these concerns, ranging from urban to rural and spanning production to consumption,” he stated. Our voices need to be heard. Neufville stated that in order for their growth to continue, more resources are required, and there needs to be a shift in mindset from surviving with minimum resources to claiming a fair share of resources available.

These institutions, which are historically Black land-grant universities, play a critical role in their communities by providing a foundation for local economies, aiding in efforts to combat food insecurity and gentrification, granting access to credit and broadband, revitalizing blighted areas through urban gardening, and actively engaging with the community. In order to accomplish this, money is necessary, and the farm bill offers the solution.